Archive for July, 2007

Beirut to Aleppo

We spent less than 24 hours in Lebanon. For years, I’ve tried to make sense of the broad outlines of politics and conflict in Lebanon for my survey courses. The main thing I understand better now is why affluent Lebanese leave Beirut for the summer. Although the thermometer registered only 93, the city was completely oppressive, a combination of 87% humidity and terrible air pollution.

We walked up the hill from the hotel, trying to find a computer with an internet connection to let kids know we’d arrived OK, passing many men in uniform carrying big guns –I hadn’t seen that many military people out on the streets since Istanbul in 1982 (that makes me quite lucky!). Everyone in this section of Beirut seems to have their own laptops. Wifi is common (seemed people for miles had come to Starbucks with their laptops), but the only internet establishment we saw was for gamers—it even had a room apparently dedicated to the incredibly popular “World of Warcraft.” Everywhere else we’ve been in Morocco and Syria, even the smallest towns, people were on Skype talking with people far away. In the Ashrafiya neighborhood in Beirut, the only cyber café everyone directed us to had no Skype, and no usable headphones to use after I downloaded the program.

The great missed photo of the night was the ABC Mall, where we had dinner. Clearly more upscale than Southpoint (in Durham), it seemed to be partly about consumerism, partly about culture, perhaps consumerism as sophistication? The point was to see and be seen, and there was much more here to see of the women. Hardly any were covered, and many were barely covered. The building’s architecture and decoration, its patrons and its recognizable logos, would have provided a terrific slide to show alongside Aleppo’s market for that first lecture, “This is the Middle East.” The juxtaposition would be accurate and appropriate, but I hope to get a chance to return to Beirut at some point–how typical is Ashrafiya?

The hotel manager seemed surprised that we were headed to Syria, which he clearly disdained. And he warned us against taking the service taxis, predicting that there would be no air conditioning and we might be sitting with people who smelled bad. We had too much luggage (six months, remember) to share a car with four others, and asked him whether we might pay for all six of the places in the car. Seemed to work out great. We didn’t notice that the car had Syrian plates until we reached the border, but we did notice that the driver was questioned at many of the checkpoints in Lebanon.

We climbed the mountains out of Beirut, then drove up the valley. There are military checkpoints every few kilometers, manned by people in uniform with weapons, sitting behind piles of sandbags.

There are visible reminders of last summer’s bombing along the roads and in the city. And the posters were ubiquitous throughout the valley: photos with names of the martyrs, photos of Nasrallah and other religious leaders. Even on posts outside churches, the posters expressed solidarity with Lebanon’s dead and Hizbullah’s leaders.

Our driver apparently brewed a pot of tea while waiting for us to show our passports to exit Lebanon. I was amazed–he kept the pot in the foot well, intermittently pouring it into a glass next to him, offering us some (good, strong, not too sweet), and sipped tea all the way to Aleppo (a 6 hour trip, including an hour at the border). The border crossing was pretty easy, except that the Syrian computers went down and we all waited a while.

Our driver had done this countless times, apparently, was recognized by many, greeted other drivers and people at the borders. He was an incredibly cautious, reasonable driver, a good thing since it seems that Syrian cars don’t have functioning seat belts. William and I were both impressed with how he changed as soon as he crossed the border. In Syria, he drove like a good-natured madman!

The hotel felt familiar after our stay for four days last summer, and we hunkered down to try to find a flat for the next five months. It was 109 here yesterday, in the shade, humidity 12%. Today, they say, we’re headed to 111. People are complaining it’s the worst heat wave they can remember. I hope that means it won’t stay this way too long.

The hotel is actually within the suq, so Friday was very quiet. On our way back from lunch, we ran into Sebastian, a local shopkeeper we met last summer. He immediately contacted his friend, who is refurbing “old Arab houses,” but, sadly, has none available. It seems most people here want to live in modern apartments and the Ottoman style houses that surround courtyards are being abandoned. In Morocco, they are being refurbed for tourists (the riad craze), but Aleppo doesn’t have many tourists. It was fascinating to see what they looked like before and after renovation, but the only one available was in the “before” state and we really do want indoor plumbing, so we’ll continue the search.

Communities and Transitions

We arrived safely in Aleppo yesterday, before I could write my last Morocco blog.

I’d been thinking about the definition and importance of communities for a while. My research is on collective identity. My friend Greg Gangi has talked about the need for community in order to create a sustainable society. I live in an “intentional community.” During my last few days in Morocco, I found myself musing about the connection between community and fear. (The first paragraph of Chris Hedges’ recent piece seemed to fit here.)

It seems that, in every Moroccan city, people leave their homes to take to the streets. They stroll, or talk, eat, attend performances–but it is striking to an American to see so many people simply out at night. I first noticed it in Marrakesh, of course, as huge numbers congregated on Jama al Fna, but that seemed such a unique place! We noticed it again in the desert city of Zagora, as people seemed to come from everywhere and walk toward the river, just to be out and among others. In Fez, we walked with Muhammad’s family along the boulevards in the center of the new city, people just walking to be out and together. In Rabat, the main street was the site of both a concert and huge numbers of people simply walking together, or sitting and drinking coffee together and watching other people walking together. In Casablanca, Katie and I were just out for a walk when we saw big groups gathering by the fountain in the square. They seemed just to be walking around the fountain, families or friends in groups. In Casablanca, as everywhere else, the large groups brought out the vendors, and people bought ice cream, popcorn, orange juice, pastries, grilled sausages, or fava beans and chickpeas sprinkled with salt and cumin. The fountain wasn’t even on for the first half hour we were there. The point seemed to be out in the evening, just to be out and among people.

At each stop, we mused on this outpouring of people into collective areas. In Chapel Hill we seem to do this intentionally three times a year: two officially sanctioned festivals and Halloween. In each case, we seem to be afraid of the appearance of huge groups of people, and make sure we have significant police presence. In the US in general, even in Kansas (my previous residence), people seem to be frightened to go out at night.

I found myself wondering about the possibilities of creating communities when we are frightened to collect informally, just to walk the streets together. And I wondered why people here seem so unafraid to be together informally, and what that implies. (Needless to say, I find it ironic that Americans warn me of the dangers of being in the Middle East; people in Morocco and Syria seem to feel safe enough to be out in crowds, while those doing the warning seem nervous even on their own streets.)

Our last day in Rabat, I found myself in the middle of a new effort to create international communities. Someone a couple of years ago created a web site for “couch surfing.” If you have a spare bed or a couch and would be willing to host travelers, you sign up. Those who have used the system post comments on the web site about their hosts/guests to discourage people who would abuse the system or endanger its participants. Some months ago, Katie tells me, the site’s founders began suggesting that local couch surfers meet. When we arrived in Rabat, Katie contacted one of the local hosts, who invited her to the first Rabat Couchsurfers Meeting, held at the park with the tomb of former rulers Muhammad V and Hassan II. I accompanied her to the event, partly because of my own anxiety. I was fascinated at this effort to create international communities.

After two days in Rabat, mostly spent walking through Sale, in gardens created by an eccentric Frenchman, and among “old stones” stretching from the Romans, through the medieval Muslims and into the present, we returned to Casablanca to the most friendly and helpful hotel staff ever. We found “Rick’s Café,” an effort to create the setting that Bogart might have presided over (they run the film nonstop in the lounge upstairs), and spent our last two days in Morocco walking (and walking and walking).

Our own community decreased in size. Ian flew back to the US to move into an apartment and begin the next semester. Katie bought a bus ticket to Madrid to start the next part of her adventure , and William and I flew off to Beirut. Thanks very much to Ian for his intermittent comments, and to both for letting me use their photos. I’ll miss them, their insights, and their humor enormously!

Fez

I awoke in Rabat Friday morning. Morocco’s capital is on the coast, and much cooler than Fez.

It’s also a good respite. I thought Fez would be one of my favorite cities. It was a hugely important political and intellectual center for successive governments, including those who had gone on to rule Muslim Spain. But from the time we arrived in the city through the time we left, we encountered young men intent on acting as “guides,” insisting on taking us to carpet shops, showing us the tanneries, walking us to the best restaurants. On one hand, I am fascinated that this informal information economy seems to work to provide income and encourage language skills in what appears to be a huge number of young men. On the other, I found the “welcome” to be completely overwhelming and the men to be more ubiquitous, persistent, and impossible than any I have ever met.

We did get to see (and smell) one of the places they tan and dye leather. Walking without a guide, we ended up actually on the tanning floor, with the huge vats of “natural” chemicals and the overpowering smell of animal hides. We were invited further in, but politely backed out and found our way (with half a dozen “guides”) to the terrace overlooking the work. It reminded me of the Met’s film on Al Andalus, and I wondered if this part had been filmed in Fez. (A nice man with a basket of mint stalks hands them out to visitors on the way up the stairs. Thank you!)

The old city is huge and quite amazing. One of my unsung skills is getting lost, and Katie insisted on taking advantage of it before we left. The two of us started out heading down into the suq, then wandered off onto side streets, an hour and a half of wrong-directional walking that took us into dead ends and terrific courtyards. It seems the “guides” stay on the main road, and quite nice people actually live in the city. We were offered a ride by an old man on a donkey, who grinned at us and said, “Taxi?” We giggled with two 10 year old girls who thought we were hilarious and tried to speak to us in brand new French. Katie called me over to look in an open window in an otherwise completely blank wall–someone’s breakfast was laid out in a nicely tiled kitchen. After being consistently harassed by street men, it was wonderful to see that there really is a city back there. (There are truly advantages in this talent of getting lost!

The best part of our time in Fez, though, was spending the day with William’s Arabic teacher and his family. They live in NC during the school year, and spend many summers in Fez and surrounding towns with their families. Muhammad walked with us in the morning (the “guides” even hit on Moroccans!) and, with his wife, picked us up in the evening to take us to his mother’s house for “tea.” “Tea” includes coffee, mint tea, pancakes, croissants, doughnuts, and a huge array of cookies. We were delighted to get to meet Muhammad’s mother and sister, his wife and two children, both completely bilingual. They took us to the main street of the new city, quite crowded with Fassis walking up and down the streets, enjoying the cooler evening and the city’s wide streets and many, many impressive fountains. A local band played music at a street festival showing off some of Fez’ traditional crafts, and one could even buy tickets for a miniature train ride through the streets. We were all thrilled to get to meet William’s teach, a quiet, kind, and religious man–I’m told he is also a terrific teacher. And I really loved his wife and was grateful for the whole family’s kindness.

The other high point of our time in Fez was the local restaurant-in-the-wall. Just at the entrance of the suq, there are a whole series of little “restaurants,” more like storefronts with a sink and a couple of burners. It is amazing what they produce from such minimal equipment. We all love street food, and this man’s cooking was terrific! We managed to have three meals he cooked during our four days in Fez.

We hired a car and driver one of those days to go see the Roman ruins at Volubilis (Walili), the tomb of Moulay Idriss (great-grandson of the Prophet, credited with bringing Islam to Morocco), and the former imperial capital, Meknes. All three are in the mountains west of Fez, set in beautiful country that is also incredibly fertile. It seems most of Morocco’s wine is made near Meknes. This was the only place we had seen large-scale wheat farming. And the olive and orange groves were quite impressive.

Katie is touring the edges of the old Roman empire (thanks, Cecil!), and Volubilis made an impressive addition to her list. There are actually mosaics still left on the ground, between the fallen-down walls. The city remained in use until the huge earthquake in the mid-18th century finally destroyed it.

We couldn’t see much of the tomb, Lyautey’s influence again, but the town was quite nice. In Meknes, too, the chief site was closed to us (the one day a year that marks the death of the saint), but we did get to wander the city some and visit the remarkable structure that used to house the 12,000 horses of the ruler. The place feels as if it is air conditioned. Our house in NC is heated by heating water that is pumped through pipes in the floor. This place is cooled by sending cold water from a nearby spring through pipes under the building.

Yesterday we walked through Rabat. The old city is quite small, and it leads to the old kasbah overlooking the Atlantic and the river separating Rabat from Sale. Lots of people enjoying the water, swimming, surfing (Californians would be pretty dubious about calling it “surf”), sunbathing. We walked through the overgrown but impressive Andalusian gardens, then all the way from the northern tip to the southern end of the city to see the Archeological Museum and the Shallah (Chellah), the old Roman city.

Like Fez, the new city is crowded at night. Throngs of people walk through the main streets. There is a thriving “informal economy” of people who spread out their blankets selling books, jewelry, shoes, clothing. A stage had been set up, and a sound system. A DJ was creating techno music while a very enthusiastic man with a microphone was doing a call and response performance with his audience.

Berbers on the Train

Trains don’t go to Essaouira, so we made our way back to Marrakesh just long enough to buy train tickets and food for the 7 hour ride to Fez. William managed to get the man squeezing oranges to fill the 1-liter Carolina Speakers water bottle while Katie and I bought bread, cheese, yogurt, and cookies.

There were two men in our compartment by the time we got there. I can’t remember how the conversation began, but one of the men, a physician, told us that the big problem in Morocco wasn’t religion, it was suppression of Berbers. He was unimpressed with the new effort to teach Berber in the schools. He was reading an Arabic newspaper, so I asked whether there were any Berber papers. He said no, it wasn’t important, and anyway, there were so few Berber intellectuals. I began trying to explain about Benedict Anderson and his argument about language, literacy, and culture being central to the development of national identity, but couldn’t find the words in any common language to convey the argument.

When the two men got off some hours later, we took over the whole compartment. I was half way through the book Ian had given me (Gaimon’s Neverwhere) when a young man took a seat with us. He told us that he taught History at Kairaween University, and proudly showed us photos of his wife and six-year-old son. I was completely delighted to meet a colleague, a Moroccan historian, so I asked him what he taught. I couldn’t quite understand his answer. I asked him what his research was about, and he seemed a bit angry. I decided he must be a graduate student, who didn’t want to talk about how his research was going. Then he explained that he really taught young children. Katie handed me the Lonely Planet guide, pointing to the paragraph that read, in part,

I didn’t pay much attention, and I was really curious. How do you explain Moroccan history and Berbers to your students? I asked. Well, he answered, there are Berbers in some places in Morocco. They live in caves. And some still live in the Rif mountains and a few places in the desert. My parents are Berber, he continued, and they taught me a couple of Berber words. He went on to confuse the basic chronology of Moroccan history, and I finally became suspicious. Poor man. It hardly seems fair to encounter a historian on a train when you’re just trying to get hired as a guide.

We have encountered “guides” in many places in Morocco. It is fascinating to hear them tell stories about places. Some seem quite freely to make things up that they think their employers would like to hear. Fiction as history does seem quite entertaining!

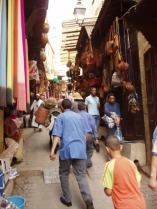

We spent our first day in Fez wandering the streets of the old city, literally downhill into the suqs. Main street of the old city survives as a major shopping area for local residents. You can find not only clothing here, but also shops specializing in buttons, others selling trim, one selling spectacular upholstery fabric. All the shops are small, and the variety of food, hardware, kitchen goods, clothing is quite astonishing. There are young men at every information sign posted, all offering their services as guides. Many of the monuments in the old city are also located in this labyrinth of streets, many in the process of being restored, a great thing unless you’re a traveler who wants to visit them. We did get a glimpse of the tomb of Moulay Idriss, and stood in the square of the copper-sellers where local lore has it that Leo the African stayed for a while.

The French legacy in Morocco seems huge today. I mean, in addition to killing many people. They created a category called Berber. They built new cities right next to the old cities, and I’m really curious about the consequences on the local urban and economic fabric. And Lyautay decided that non-Muslims were not to be permitted to go into any mosques. Was he worried that Christians would convert? Was he worried that they would take over the mosques and Muslims would be angry? Concerned that their own soldiers would desecrate holy places? Throughout Turkey and the eastern Mediterranean, it seems, anyone can go into mosques, a policy consistent with the historical universalism and interest in conversion that Muslims have embraced. Over many months with art historians during my dissertation research, I visited and admired many Ottoman mosques. Some French colonial ruler decided that Muslims should not enter mosques, and Moroccan officials seem to believe simply that this is the way things must be. So we have not been able to see, appreciate, admire any mosques in Morocco.

Full Circle

Full circle, back in Marrakesh for two nights to return the car, regroup, and plan the rest of our trip. This time, Marrakesh felt more familiar, certainly cooler, than it had seemed when we left it. Now we had traditions, strange as that seems. Back to the Jama al Fna for dinner, harira first. This time, the man who had been pressing William a week earlier won out, and we had dinner at the booth of the one who always talked about Thomas Hardy and English writers. After dinner, as we moved off to listen to a group of drummers surrounded by a circle of spectators, our host pulled William aside. “You don’t believe me, do you? I studied English literature.” He pulled out his notebook and began reading his own poetry.

Bahia Palace the next day, another structure with outrageously impressive ornamentation: carved wood ceilings, carved stone decoration, zilij tile mosaics, inlaid marble floors. In 1912, French officers took it over as their Marrakesh headquarters. Only part of it has been restored, part is now used by the King.

When it began to cool off, we spent a bit of time in the market next to the square. Katie bought a new purse to replace the one she got last summer in Turkey, worn out from a year of constant use. This one had already begun fraying. We picked it up from the man who had sold it to her. Muhammad talked with us about fabrics and prices, then sent us down the shops to a man who sold very nice jalabas. This shopkeeper used to be a Math professor, but when the university switched from French to Arabic, he explained, he couldn’t continue. “I’m Berber,” he explained. Now a designer, seller and exporter of caftans, jalabas, jackets, and blouses, he loves his current work.

For our last evening, we returned to the square, to the booth we had visited our first night in Marrakesh. Her husband told us that Rashida, one of the cooks and the person for whom the space was named, began as the first woman cook on the square 24 years ago; she was still only one of two women who worked at the food booths. She has a huge smile, a big hat, and I’m sure she must have heard me that first night exclaiming that we needed to go to the booth with the woman cook–she seemed terribly amused then, and again seeing us a week later. It seemed the crowds had grown even larger, and there appeared to be more musicians. But the performer that still intrigued me most was the story-teller. Constantly surrounded by large audiences and accompanied by three musicians, he seemed every night to delight his listeners with new tales. They smiled, then laughed, grew serious. Watching their faces was quite remarkable. The square has been named a UNESCO World Cultural Site for the oral traditions on the square. I wish I could tell stories even a small part as well as he does.

Greatest missed photo: the woman covered in gray from head to toe, only her eyes visible behind eyeglasses, gloved hands, riding a motorbike.

We lost power around 10, as we were packing to leave Marrakesh. That meant an even earlier start for the bus station. We waited to check our bags as the ticket man greeted his friend, who showed him the front page of the paper: photographs of Morocco’s king, Osama bin Laden, and Ayman al-Zawahiri. Both men told us how angry they were–bin Laden, they said, was not only targeting the King for encouraging Western tourism, but targeting the whole country. It seems this does not make friends, at least among some newspaper-reading Moroccans. Goats in trees on the way to the coast. We walked all the way through the walled city of Essouira to arrive at our hotel, in a courtyard not far from the Atlantic Ocean. This beach town is a fraction the size of Agadir, with small hotels and easy beach access, a former Portuguese naval stronghold from the 17th century. If Casablanca is the white city, and Marrakesh the red city, Essouira is the blue and white city.

It was a wonderful weekend, a much-appreciated break from the heat of Marrakesh and the desert. Essaouira still seems to be a small fishing town, with lots of tourist infrastructure. Unlike Agadir, though, most of the tourists seem to be Moroccan families. An early morning walk on the beach, where groups of twenty- and thirty-something men were playing soccer, a lesson in making mint tea from a 14-year-old teacher, walks through artist galleries and along the city’s ramparts, watching Moroccans on vacation–a good, quiet weekend before moving on to Fes. We celebrated our anniversary at a small restaurant; when we told our young waiter it was our anniversary, he grinned enormously, and wished us a large family!

Observations from the Road

Goats sometimes stand in trees.

It is possible to make a left turn across three lanes of traffic.

Maybe lane lines are a hindrance.

Upscale restaurants play bad American 80s music.

The tea is great (hot, sweet, minty and green), but don’t expect to find good coffee in a Berber village.

It’s cool to be Tuareg, or at least Berber and nomadic, especially if you want to sell jewelry.

“Share the road” is taken seriously in Morocco.

Love the tagines, but I miss the Ottomans at dinner.

Back in Marrakesh, which now feels welcome and familiar. A week of driving introduced us to terrific people, wondrous places, amazing sights. We stayed in quiet places, villages where internet was available only 27 kilometers away, where there were only two satellite dishes (ubiquitous in most of the country), where we saw large groups of women walking together along the streets up the hillsides in their best jalabas, obviously going to some celebration. We saw the remains of the Glaoui Pashas’ efforts, the beginning of the desert, sustainable small-scale farming, and markets that were unlike any I had seen. Throughout the small towns of the south, people have organized into cooperatives to make and sell crafts and agricultural goods. There are many cooperatives specifically for women. I have no idea how successful these are in alleviating some of the poverty we have seen in Morocco.

Driving here is a remarkable experience by itself! Any vehicle is assumed to have use of the entire road, especially the middle, until meeting another vehicle. Our car’s gears were a bit old, which made driving through the mountains even more exciting. Towns brought different challenges. The roads are used by children playing, people walking, sheep and goats crossing, bicycles, motorbikes, and donkey carts. Considering the huge numbers of people and animals on the road, and the propensity for cars to try to pass on hills, curves, and across many lanes of traffic, it is quite remarkable that we saw no traffic accidents. The system really does seem to work: everyone, drivers and pedestrians, expect driving to be a fluid project. Rigid lane markets would be quite unhelpful. William actually drove in the old city of Marrakesh as we returned, where you can reach out and touch someone, and someone else, and their donkey, from the windows of the car.

When we blew a tire on the highway, we found that tires have many lives in Morocco. There seems to be a resale market for tires–the owner of our car was surprised that we actually bought a new tire to replace the old. The third time around, tires are made into the buckets that we saw for sale in the markets in the south.

We got pulled over once for speeding–lots of police check points and speed traps on the roads here. The officer was astonished that we really didn’t have enough dirhems to pay a 400 DH ticket. He explained that he couldn’t take all of our money–what if we needed some down the road? So he took 200 DH and sent us on our way.

I asked Ian to write about the remarkable music he and Katie have been groaning at when we go to mid-range restaurants in Moroccan cities. “So, about the restaurant music here. Let me just say that I haven’t heard a DJ as bad as whoever makes the music mixes for upscale Moroccan restaurants since I stopped going to middle school dances. So in the last six or seven years. Every single mix includes Hotel California-which is a good song, don’t get me wrong, but it seems a little strange to constantly have it stuck in my head while traveling in northern Africa. Especially since I didn’t bring my ipod. They also love music from the eighties-particularly Brian Adams, Rod Stewart, and Sting; every time we eat at a nice restaurant, we hear at least two of the three. And there was one song last night that I swear I wanted to get up and start slow dancing to. Middle school slow dancing; that’s what it reminded me of. So, if you’re going to a nice Moroccan restaurant, expect great food, great service, and good decor. But absolutely terrible music.”

Goats in trees are part of the process of creating argan oil, which seems to have many medicinal, cosmetic, and culinary uses, recently in much demand in Western cities. The argan nuts have a coating which can most easily be dissolved by the digestive system of a goat. At harvest time (now), the goats are in trees eating the nuts. Farmers acquire the seeds from goat dung, and press them into oil. I admit to being less than excited about eating the salads advertised as coming dressed with argan oil.

Alas, the Ottomans never ruled Morocco. Dinner here comes either grilled or cooked in a distinctive pottery vessel, a tagine, that apparently turns a stovetop into an oven. Moroccan food is terrific, but the lack of Ottoman presence is quite apparent in the menu. All over the eastern Mediterranean, rice is served hot; the milk of sheep, goats and cows is made into white cheese; fermented milk (yogurt and dried yogurt) are important dietary staples; and the leaves of grape vines are almost as important as the fruit. Throughout Morocco, rice is served cold, I haven’t figured out where milk goes (except to baby animals), and people seemed shocked to think that one could roll food in leaves.

Zagora

Zagora is hot. Russ looked it up online: at 6 pm, he said, it was 102, presumably in the shade. But there isn’t much shade.

This was the end of the line–or the beginning, depending on which way your caravan was headed. I remember reading that the Sahara was more like an ocean, encouraging, not forbidding, trade. People, merchandise, ideas, styles passed through the desert for centuries. The diversity of clothing style and skin pigment make the centuries of connection quite apparent. Like Timbuktu at the southern end, Zagora at the northern end became a center of Muslim learning.

We were there not only because it’s the northern end of the trans-Sahara route (a sign on the south side of town claims it is 52 days to Timbuktu–see above, with Ibrahim). William had spent a month in the town in 1995 and wanted to go back with the family. We arrived Saturday evening and immediately met Ibrahim, one of the men he had known 12 years earlier. Back then, William had asked where he could get a black shesh like the one tied on his head; Ibrahim immediately sold it to him.

Zagora has expanded enormously in the intervening decade. The city to the south of the gates has remained six blocks wide and a few long, but a huge amount of building has gone on north of the gates. And a large, apparently brand new regional army headquarters has been built between the town and the river.

Saturday evening, we went with everyone else to the river. Groups of young men walked and rode motorbikes along the road and the river. We saw a couple of older men doing their prayers by the water. Young women walked together, the variety of dress still surprising me. Western clothing was everywhere, shirts and trousers on both men and women. Both also wear jalabas, long gowns with hoods hanging down the back. Some women wear a very long piece of cloth that is tied so it looks incredibly graceful as they walk, functioning simultaneously as a skirt, shawl, and head covering. Women with bare shoulders walked and talked with women who covered their heads, as everywhere we’ve been so far. The European and American effort to class covered and uncovered women as two distinct groups seems quite far from the mark.

Ian writes to describe the market we found on Sunday morning in the center of Zagora. “The market was like something out of a movie scene-you know, the one where the main character is looking for something in the bustling middle eastern market. There were rows and rows of stalls selling all kinds of things, from garden implements to music to spices to ten foot poles and ladders to produce to buckets made out of old tires. Some of the stalls were covered with expanses of slanting burlap, but most of them were open to the sun, and the heat baked the entire scene. Even more interesting in some ways than the things being sold were the people there to buy them. You had an absolute throng of humanity there, with covered women wearing elaborate and beautiful wraps brushing past young men wearing US army surplus pants that were too short for them with Charlotte Hornets t-shirts. You had men wearing jalabas and turbans with big knives stuck in their belts, and other men with impressive beards that looked like they hadn’t seen a sharp edge in months. It was an absolutely incredible scene.” William bought one cassette tape he heard playing in the market.

The sun was overwhelming, and I had to quit before the others were quite ready. After a brief rest, we drove south to Tamegroute to see the library. I don’t know anyone who has worked in this library, but Lonely Planet makes it seem an incredible resource for medievalists, with a collection containing “illlustrated religious texts, dictionaries, astrological works”the oldest dating to the 13th century. The town was a religious center from the 11th century, and the zawiya (17th century) includes a mosque, a school, a tomb, and the library. We couldn’t get in–we waited until it was supposed to open at 3, then were told that the person who opens it was busy. We did see the school’s courtyard, then drove far enough south to see some dunes and collect some Sahara sand.

When we returned to town, William went in search of his friend Lasan, who had managed the establishment where he stayed for a month more than a decade ago. He found Lasan in great spirits–his Japanese wife had just had a baby girl in Japan (a bit early) and he would be leaving in a few days to join her and hold their first child. We all went to his new “camping” to meet him, an incredibly warm man with a huge smile and lots of energy. He insisted we stay for coffee, and told us about his new apartment he was finishing for people wanting to stay longer-term in the new establishment he owns south of town. (Looks like a great place to stay to do research in the nearby library.)

Leaving Zagora was a bit difficult. We had planned to drive to Taroudannt, but the small, walled town (street sizes to population about the same as Avignon during the summer festival) seemed just overwhelming after the small mountain and desert towns, so we kept driving all the way to the Atlantic. William got to show the kids how to change a tire by the side of the road.

Taroudannt had been teeming and crazy busy on market day. Agadir was busy in an entirely different way. It is clearly a very successful tourist resort city. We heard very little Arabic, and walking along the waterfront (which one couldn’t get to because of the huge hotels) we saw an English pub, a taco restaurant, an invitation to supersize one’s meal, many boutiques. The new Agadir seems a European resort more than a Moroccan city. It does have a constant reminder of its past, though, in the huge mound that reads in Arabic “God, Country, King” slightly to the north of town. The 1960 earthquake did such extensive damage that people moved the city instead of trying to reconstruct it.

The South

We rented a car on July 4 and drove south. Our first stop was Tellouet, kasbah of the Glaoui Pashas, whose collaboration with the French first elevated then destroyed them. The kasbah was pretty impressive. It had been home to a very large household of guards, retainers, family, and servants. The first structure, now in ruins, dated from the mid-18th century. The custodian took us around the most recent building, completed only in the 1940s, with its spectacular zilij (mosaic) walls, carved moldings, and painted wooden ceilings. We got to see the second building, finished shortly before World War I, with the kitchens and guest accommodations. The French occupiers wanted a ruler who could keep the trade routes and resistant tribes in the south under control; the Glawi leaders wanted to rule the region. When the French gave them new kinds of weapons in the 18th century, both realized their desires. For almost two hundred years the Glaoui Pashas ruled the region, putting down rebellions and securing the routes. They built fantastic kasbahs, the latest of which was the one we visited at Tellouet. But when the French were thrown out after World War II, the Glaouis were destroyed. In the Middle East, collaborating with foreign occupiers brings rewards only as long as the occupation continues.

From Telouet we drove through Ouarzazate, the Hollywood of Morocco. As we turned around each bend in the hghway, it seemed, we saw a new scene straight out of the Orientalists’ fantasies: palm groves against desert backgrounds; kasbahs rising out of the mountainsides, nomads’ tents pitched in the rocky desert. The movie industry has taken advantage of the scenery, filming blockbusters based out of Ourzazate. Star Wars’ Tatouine seems to have been near Ourzazate, parts of Lawrence of Arabia were filmed here, Alexander the Great, Gladiator, and the list goes on. We drove on to Ait Benhaddou, where we checked into the hotel where David Lean had stayed while filming Lawrence of Arabia. The hotel was right across the valley from the old village, restored for use as a film set. The population of the village had moved down the road a bit to a new site with electricity and running water. We would see this again: the old village site was abandoned as people moved into newer buildings close by, still near their fields, to take advantage of the amenities that make life so much easier. The old buildings, made of mud bricks, gradually fall back into the ground.

We were in Berber country, and spent the next few days driving, walking, and meeting people in villages set among spectacular mountains, perched over dramatic gorges, and overlooking miles of palm groves. Berbers. Daoud, who speaks at least five languages and leads tours in the desert in his new Toyota Land Cruiser, claims they make up the majority of the population of Morocco. The children of his village learn Arabic when they begin school; within a few years, they will learn French and English at the secondary school in the town 27 kilometers away. (They come back to the village for weekends and holidays.) Only in the past few years have the schools taught literacy in Berber, a result, he claims, of the new King’s mother’s ethnicity. I asked about this term, Berber, introduced by the French to indicate non-Arabs, in order to try to divide the local people against each other during the colonial period. Daoud explained that there are actually three distinct groups, which they distinguish among themselves. For outsiders, though, they seem to have accepted the name Berber. But the effort to divide Moroccans wasn’t successful. This seems different than the Kurds, who claim to be “from Turkey,” . “We are Berbers,” he told me (and we heard again and again), “and we are Moroccans.”

Muhammad, a friendly man we met in Todru Gorge the next day with a bum foot and a bit of English, offered to took us on a walking tour of the palm grove, and in the process explained a bit about how their town worked. From above, the palmerie looks like a simple grove of palm trees along the river. Inside, it is an extensive garden with a very complex organization. Each family has a part of the property to farm. Even if one sells his/her house in the village, the land stays within the family. The irrigation system is extensive, long main channels flowing from the river, and subchannels into each field. People are growing tomatoes, peppers, mint, alfalfa, potatoes, wheat (just harvested), cabbage. We haven’t seen any of the parsley or cilantro so often in the food, but mint grows everywhere on terraces or in yards as well as fields. Muhammad explained that the trees (almonds, walnuts, date palms, pomegranate, figs, peach, apricot) are available for anyone to come, pick, and eat, but you can’t take the fruit away. The guy in charge (the chief or sheriff of the palmerie, William couldn’t figure it out and neither could I) would demand payment for things you take that aren’t from your own garden. He would also fine you if you stepped on someone’s fields–we walked on the raised areas between farms. I don’t know how he is appointed, but it seems he sees all. It’s much cooler in the palmerie. I was impressed with the number of people down there. It was hardly a place to be alone, though it appears both hidden and private. Many children were playing–a group of boys seemed quite excited about a snake they had caught in one of the irrigation channels. People farm in what we have come to call French style; the double-dug gardens with partly raised beds are planted close together to discourage weeds. The soil is so rocky, it must have been exhausting to create such an extensive farming system, especially when the main implement is a device that looks like a hoe, but with a head the size and shape of a shovel.

We had arrived on threshing day. Katie, Ian and I, out for a walk in the afternoon, stopped to watch as men attached a mechanical thresher to the Massey Ferguson tractor. Women carried wheat stacked along the road in hand-tied bundles to the thresher, and a man in his late 20s wearing a sunhat fed the bundles into the machine. Two women at a time carried grain away in baskets, while more women put the next basket under the thresher. The hay came out into a large sheet they had attached to the other end. Women carried huge bundles of the straw attached to their backs in these sheets–I wondered whether more pack animals would be what they wanted most.

We stood a bit away on the shadier side of the road to watch. Other women were using short straw brooms to sweep the street from the previous threshing across the street, children and old men were watching, along with the men who brought the thresher and tractor. One woman smiled and suggested we help, which, to their apparent surprise, all three of us did. After a few armloads, they indicated we should stop and seemed amused and pleased. Katie took a few photos of the threshing. Daoud told us later that night that he had been helping his own family with their threshing earlier in the day–each family plants and harvests its own wheat and brings the bundles to the road. Each family pays for the use of the thresher.

The kids and I had talked earlier in the day about how much more difficult this process is without combines: in Kansas, the wheat stays in the field and the combine cuts it in place, separates the grain from the straw, throwing both into separate trucks to be driven off. Here, the family has to cut the stalks, bundle them, carry them to the road, feed them to the thresher, carry off the grain in baskets and the straw in sheets. But in the evening, Daoud talked about how easy the new process is! His family used to have the donkey walk for hours on top of the cut wheat. Then, he explained, you had to spend hours going like this, moving his arms together quickly over his head. The thresher really made the work much easier. Families sometimes had enough for their use all year, sometimes more and sometimes less. The grain was milled into flour in a nearby village, and the flat, round bread people eat here is baked in the local hammam.

When we left Todru Gorge for Zagora on Saturday, temperatures had climbed. I thought we were just unaccustomed to the heat, but the hotel manager explained that the heat wave had begun three days earlier (about the same time we left Marrakesh), and would likely continue for three weeks. The man who sold us water at a gas station as we headed out of town asked how we were tolerating the heat. With that send-off, we headed south, toward Zagora in the Moroccan Sahara.

Gardens and Squares

Gardens are a big thing here. Seems any available space has plants. The roof patio of our lodging has plants so vigorous that we need to push away branches to get to our door. We sat at lunch on a terrace overlooking the Saadi tomb complex and the storks that have made their homes on the walls, and saw cactus gardens on a neighboring roof. The sun is very hot, the city is very dry, and the green seems to be everywhere, and everywhere welcome.

Yesterday we walked all the way into the new city in the continuing search for Katie shoes. Then we walked, and walked, and walked up Muhammad V Street, trying to find the Majorelle gardens. Built by a French artist expatriot in the early twentieth century, we had read about these gardens, and they sounded better and better as we walked past the large (red) hotels, office buildings, and malls of the new city. By the time she saw the gate, Katie said, she just hoped that’s where we were headed because she would have entered in any case.

The garden was spectacular. We have a fiddle-leaf ficus that pretends to be a climbing vine in the two-story front of our house. This garden has one that must be a 60 foot tree with a huge trunk. Turtles and large goldfish swam in the water-lily pool. The cactus collection was amazing, situated in the center; the bamboo forest was around the edges. The Museum of Islamic Arts attached to the garden had terrific examples of Moroccan doors, jewelry, carpets, and very old pottery.

We decided in the afternoon to try to find the Suq Cuisine [sic], but instead found a commercial area of the old city that had no other apparent foreigners. I’ve always loved getting lost. One man found us and led us to the most remarkable collection of herbs I’ve ever seen. It was a wholesale place specializing in remedies, perfume ingredients, even incense.

Back to Jama al Fna for dinner last night. We ate our harira (soup almost as good as Sahar’s version) at long tables with many other people. Then wandered looking at the various options for dinner. (“Ali Baba! Ali Baba!”) We tried to figure out the nature of the various stalls, some were empty, others completely full. The most popular was selling merguez sausages to Moroccans two lines deep. Moroccans were also patronizing the shops with sheep heads and boiled egg sandwiches. We chose the only one that had a woman cooking; they sold vegetables, grilled fish and kababs, all quite good. Katie decided to try cinnamon tea and cinnamon cakes, which this young man was delighted to provide. It was so strong I could barely sip it.

The crowds were even bigger last night. The celebration on the square is clearly for the people of Marrakesh, and the biggest audience was for a story-teller accompanied by two stringed instruments and a drum. Foreigners are warmly (sometimes too eagerly) welcomed, but the show is hardly for us.

Today it was the Saadian tombs and palace. The palace was quite destroyed, but workers were putting up stands and a stage for the music festival to be held here next week. The tombs are quite remarkable. All the artistic elements I associate with Spain were, of course, present at the tombs and in the restored minbar housed inside the palace complex. Muslim conquerors came in waves from Morocco to conquer Andalusia and put a stop to the decadent lifestyles of earlier Muslim rulers of Spain; as ibn Khaldun found, it took only a few generations for each to begin their own massive building and beautification projects, inviting another group with pious rigor to take over.

A remarkable scam artist met us at the entrance to the old Jewish quarter. He was trying to explain Jews to us. You know, Jews pray at a synagogue on Saturdays (“Shabbat Shalom” he added), Muslims pray in a mosque on Fridays, Catholics pray on Sunday. Where do the Catholics pray? I asked. On Muhammad V, he answered.

Marrakesh

William (a.k.a. Ali Baba) seems to be viewed as a rock star here. Everywhere we walk, people call out to him (Ali Baba, Ali Baba) smiling. He returns their enthusiasm and their affection, clearly feeling quite comfortable in the remarkable, stunning, singular environment of the old city of Marrakesh.

If Casablanca was a white city, this one is clearly the red city. Instead of white buildings, even the new high rise hotels, old city and new, are painted red/pink. Casablanca seemed little different than any other European or Middle Eastern city I had visited. I have never seen anything like Marrakesh.

I asked Ian to describe the scene for me as we left one of the suqs, and realized it would hardly be believable. I get what all those Orientalist travelers were about—it isn’t difficult to portray this place as completely different, as everything non-Europe.

Of course, it isn’t. The residents of Marrakesh eat and sleep and shop and have families and pray and work. But they do it in such style!

Jama al-Fna is the center of the old city. It seemed a pretty calm place when we arrived in the afternoon for coffee. It’s only a few meters from the place we’re staying, an old house converted to a 12-room bed-and-breakfast. To get to the square, we had to dodge bicycles, motorbikes and donkey carts. (Ian jumped aside for an oncoming fez-wearing man on a motorcycle; I remarked on the young covered- “veiled”- woman roaring down the street on hers.) At four, the square hosted half dozen orange-juice sellers (fresh juice is 3 dirhems; a dollar is 8 dirhems).

When we returned around 8 pm, the square had been transformed. It was jammed with tourists and locals. (William commented that we had seen more tourists here in the few blocks from the train to the hotel than we had in three days in Casablanca.) We walked through rows of tables and lines of food-purveyors that seemed to have appeared out of nowhere. (I have to watch this process!) We were greeted at each invisible line dividing one establishment from the next, each host inviting us to sit at his table. Men sold snail soup from large pots, fried fish, grilled meat, couscous combinations, cooked sheep heads. The smells were as overwhelming as the crowds. At each table, it seemed, men came to greet William, grinning, urged him to eat at the closest booth, grabbing his hand, demanding his friendship. It’s probably no more than they would have offered anyone else equally interested—and William quite obviously loves this place and these people.

Away from the tables, women offered to henna our hands, to tell our fortunes. Men sold herbs for a variety of uses. Beggars set themselves up among all the others on stools and blankets around the square. Groups formed around men who told stories, did acrobatic feats, played music; when the performance ended, another circle formed around another performer. But a snake charmer? The naked little boy of the Said cover (Orientalism) was, thankfully, not part of the scene. But if one is looking for the mysterious east of the old Orientalist travelers, Marrakesh seems to be the place to find it.

For our young geographer Katie, Jama al-Fna is a wonderful example of the potential use of public space, more varied than a Prague beer garden, more extensive than an American street festival. She grinned, reminded me that she is energized by this kind of public event, and began speculating about how late she might be able to stay awake tomorrow night.