Archive for November, 2007

Ruwwad

Razan picked us up at our small hotel, and as we drove past the KFC’s, McDonalds, gleaming new office/shopping plazas, and continuous construction of West Amman, she told us that she had worked for GE when she graduated from the university. Two years into the job, a friend asked her for a ride to Ruwwad to tutor that day. Curious, Razan went inside and began reading to some of the children. She promised to return the next day, and soon was a regular volunteer. Months later she had left GE to become Program Coordinator at Ruwwad.

Ruwwad is located in Jabal Nathif in East Amman, across an invisible boundary between the eastern and western part of the city that seems to divide very different worlds. The area has been populated mostly by Palestinian refugees since 1948. The people who live here are very poor, but since the place was never designated as an UNRWA facility, they get no help from UN funds. Until Ruwwad provided the space, the Jordanian government provided neither a health clinic nor even a post office. The government has just recently promised to create a police station. The schools were unimpressive, in sum, Jabal Nathif was a very “under-served” area. Ruwwad has done more than offer services. It has allowed the local children to think about opportunities that they could not have even imagined two years ago.

Ruwwad was Raghda Butros’ dream. When we met her in 2003 she was a Humphrey Fellow at the University of North Carolina, in transition between jobs. After she returned to Amman, she decided she could actually carry out her project. Of the many things I admire about this woman, one is her ability to do things that I would find unlikely at best, and probably impossible.

When we first saw the Ruwwad site in the summer of 2006, there was little but a shell of a building and Raghda’s dreams to fill it. Now, Razan was taking us through three stories filled with children, volunteers, staff, and a flood of remarkable ideas they seem able to implement almost as soon as they arise. Raghda explained that the staff had decided to move its offices out of that initial colorful structure, leaving the first building to the programs and the children who had, by that time, moved into every inch of it. They found that the children followed them into their offices in a neighboring building-–Raghda’s has not only the desk, books, and computer one would expect in an NGO director’s space, but also puzzles, books, and bean-bag chairs for the children who drop by to hang out while she is working.

Ruwwad opens into a library full of children’s books. (They could always use more…) It is brightly painted, and furnished, like most everyplace else in Ruwwad, by the refurbished castoffs that the volunteers and staff collect, clean, repair, and decorate with great imagination. (The kids even designed the ngo logo.) After an existence of less than two years, Ruwwad’s two buildings today offer a computer lab, a library, courses, a preschool, a furniture-refurbishing shop, and a large meeting space.

The programs that fill the place, though, are the most exciting. “Windows” offers local kids an opportunity to do art, usually available only to Amman’s wealthier children. Adults attend literacy classes in Arabic and English classes offered by volunteers. The large conference room on the top floor is the setting for monthly discussions about topics chosen by local high-school and college-age students, conversations often taboo and unbroached at home or in school.

These older students are often recipients of Ruwwad’s scholarships. Each scholarship student, in addition to attending community college or university, is required to volunteer for the organization. These volunteers provide the labor needed to improve local homes and to build new ones (with the local Habitat for Humanity chapter).

Rami was with us as we toured the facility. At 17 and in 11th grade, he has made a gradual transition from a local ringleader to one of Ruwwad’s big neighborhood supporters. His friends have followed him, providing a huge support to volunteer efforts to rebuild the community. He came along as we went to a neighbor’s house for sweet, minty tea. Our host has four daughters and three sons. The youngest child, Sarah, is four months old.; the oldest is in her 20s. We met three daughters, including one about to take her exams to get into the university. The family’s house used to consist of one room, an entryway beside a small, walled-off toilet, and a moldy kitchen. After Ruwwad’s volunteers moved the toilet onto the patio and installed a shower, they recreated the entryway into a second room, essentially doubling the usable size of the house. And they treated the mold and repainted the kitchen. Our host, now in her 30s (she married at 17) seemed quite delighted–and delightful. After tea, she urged us to stay for coffee and lunch; when we declined, she insisted that we return another time.

Still less than two years old, Ruwwad now employs 23 people. The programs seem both remarkably innovative and very comprehensive. I keep deleting the words here, because I seem unable to convey the complexity of the program that Raghda and her staff have created. I am used to writing in a linear way, but the varied parts of Ruwwad’s program seem so connected to other parts, it would be more comprehensible with a diagram than a paragraph. I’ll try to give a sense of it. Their varied activities enrich the lives of residents physically (improving living quarters, providing job skills through volunteering, and finding funding for urgent medical situations); academically (offering scholarships, tutoring, literacy programs, English lessons, and encouraging reading); socially (providing volunteer opportunities, creating community cohesion, offering youth a space and resources to talk about important issues); and emotionally (improving living conditions, creating community, responding to urgent local needs). All who benefit are expected to give back through volunteering, which, of course, provides more resources to the Jabal Ndif community. Why didn’t we all think of this decades ago?

The Ruwwad web site does a much better job describing this remarkable place.

Istanbul

It’s difficult to write about Istanbul. I arrived for the first time 25 years and one month ago as a graduate student on a Fulbright scholarship hoping to carry out dissertation research in the Ottoman archives. I’m sure that I was struck then by the strangeness of the city, the challenge of the language, the confusion that results whenever such large groups of people share the same space, to say nothing of the frustration of the bureaucracy that refused me access to the archives for three months, and the remarkable camaraderie and generous assistance of all twelve of the regulars in the Ottoman reading room when I was finally permitted entrance. (The archives some years ago moved to a larger location with better light, and when I last visited, almost 100 researchers were working there. Some things haven’t changed–I’m again waiting for research permission, this time to use published newspapers in a public library.)

I’m no longer struck by the city’s strangeness, which may be partly because Istanbul has changed; it’s probably more because I’ve fallen in love with Istanbul over the years, and perhaps because I’ve now spent time in places even less familiar.

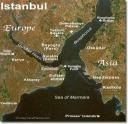

Istanbul is beautiful, stunning, shockingly appealing. We approached it this time from Anatolia, riding the train for many kilometers from the furthest suburbs into the heart of the city, then taking a ferry across the Bosphorus to the old city. The skyline has changed in the past 25 years–sort of. To the right, there is a second bridge connecting Asia and Europe; straight ahead there are large skyscrapers jutting above the older buildings. To the left, though, are those seven hills and their spectacular domes and minarets. At the risk of sounding like one of those nineteenth-century Orientalist travelers, I admit that the view of the old imperial capital from the water is breathtaking.

I had three goals for this trip. I wanted to spend time with Katie, who is teaching English in Istanbul; I needed to talk with colleagues about some research questions before finishing the last chapters; and I planned to make some logistical arrangements for the student group I hope to bring with me to Turkey for seven weeks this summer.

Katie is wonderful. So is her school. The day after we arrived, she took us to see the place she works, and rumors circulated that Katie’s mother was visiting! I was reminded of that first time, when Katie was a toddler, that I heard a child’s loud whisper in an auditorium, “That’s Katie’s mom!” I’ve been quite delighted to be “Katie’s mom” ever since. Now some of her more courageous young students stood outside the door to the English department office, trying to catch a look. Two actually came inside, probably 4th graders, who ventured to answer my questions about their names and their favorite football teams. (Fenerbahçe and Galatasaray have been engaged in fierce competition this season.)

We saw her house, up five longer-than-usual flights of stairs in an old building on the Asian side of the city, in the not-yet-gentrified outskirts of Moda. Her house is in the process of becoming heated and furnished, and the neighborhood is terrific. She walks through a wonderful fish and vegetable market on the way up the hill every day as she returns home from work. She has developed a new set of friends, partly through work, partly through old friends (Katie came for the first time 21 years ago), partly through the local couch-surfing group.

William and I were staying far from the real world of Istanbul, in the part of the old city near the great monuments most frequently haunted by carpet dealers. Within five minutes of stepping out, someone finds a new and creative way to suggest you go into his shop to look at his rugs. As I found myself warning new tourists about these men, I realized that I must sound quite like them when I suggested that the new tourists go to my long-time carpet-seller friend instead to look at his carpets!

William has been sorely missing the NFL season, and we were delighted when Katie invited us to visit one of her friends and watch a Packers game. Our Turkish host was little interested, but William was thrilled.

The rest of my time was spent walking, drinking Turkish tea, talking with friends about my book, and making arrangements for the summer. That summer plan made it just a bit easier to leave Istanbul this time.

To Istanbul

We decided to try the train to Istanbul, but the closest place to get it is Adana. The bus ride from Antakya to Adana took me through places I’d been reading about for years, the mountain pass town of Belen, the port city of Iskenderun/Alexandretta, Dörtyol right on the previous border between Syria and Turkey. We got to Adana just in time to eat some spicy kebab, try the locally-favored beverage (salty turnip juice), sit in the “wait foring room,” as the sign read, and chat with the staff before boarding a sleeping car for the 19 hour trip.

The trip was so wonderful we decided to return by train, too. We were accompanied by a large group of women on their way to an Amway convention in Istanbul. They had brought huge quantities of their own food, and took over the dining car and kitchen, laughing and talking as they prepared a spicy bulgar/vegetable/hot pepper paste dish I had never seen before.

The scenery was spectacular. I’d once driven through the Taurus mountains, but was so nervous about the trucks that I didn’t appreciate it as I should have. This time, we sat watching out the window (when we weren’t watching the food preparation).

Antakya/Antioch

Our driver began speaking Turkish with me immediately. I asked how he knew Turkish. “I’m a Turk,” he answered. As we made our way through Syrian customs and passport control, he spoke Arabic with the officials. Back in the car, as we crossed into Turkey, I asked when he learned Arabic. “I’m an Arab,” he responded. We arrived in Antakya (Antioch) two hours after leaving Aleppo, half of it at the border. Before the city became part of Turkey in 1939, no border crossing would have been necessary.

The book I’m working on tells the story of how Antakya and the province around it were detached from Syria and joined to Turkey. But it focuses largely on national identities, how people decide to which national group they belong. Our driver made it quite clear that no choice actually needed to be made. He claimed that 70% of the people of Antakya spoke Arabic in addition to Turkish. Since only Turkish is taught in schools, however, many remain illiterate in Arabic.

The city seems much more than a few kilometers from Aleppo. The color is striking on the Turkish side of the border. Syria has a monochromatic color scheme: the streets, the buildings, the walls, are all made of stone, and everything is white. Turks paint their houses, sometimes outrageous colors (lavender apartment blocks?). Turkish signs and billboards are all in Latin characters. And most women don’t cover their heads on the Turkish side of the border. Turkey’s enforced secularization actually prohibits women students and state employees from covering. Women at Mustafa Kemal University in Antakya stop at a phone booth right inside the gate to remove their scarves as they enter campus. I waited to make a phone call as one student checked her hair in the little mirror above the phone. She giggled when I asked her if the mirror was hers. Apparently, it is a collective mirror for use after removing scarves on the way in and replacing scarves before going back into the street.

Our days in Antakya were enlightening and enjoyable, thanks largely to our “host,” Koray Cengiz. He runs the local university’s international exchange programs. I found him through “couch-surfing,” a movement my daughter introduced me to. Koray made us a reservation at Mustafa Kemal University’s guest house, scheduled appointments for me with local historians, introduced us to some of his friends, and walked and walked through the city with us. By the end of our visit, we had learned about the Erasmus program, teaching English in Turkey, the city, and the university. He had learned more than he had probably ever wanted to know about Antakya between 1936 and 1939.

William consults on 1936 map: Where are they now?

William and I walked the routes of the myriad demonstrations during that period, nearly all of which focused on the bridge over the Orontes River. We found the best Iskender Kebab in town (maybe even in Turkey), and sat looking at terrific photos of Antakya in 1940. Our waiter called the phone number attached to the photos, and soon we sat in the office of the photographer looking through prints he had made of his first professional shots, when he was still in his early 20s.

By the end of our stay, I became convinced I had never seen such a bi-national city. On one hand, Turkish flags and pictures of Ataturk were everywhere. I was surprised by the huge number of flags displayed, and Koray explained that flags were flying throughout Turkey in response to the recent attacks on Turkish soldiers further east. There were few remaining signs in Arabic, even fewer than we had seen in the summer of 2001 when we stayed in the city for just one night.

On the other hand, the bazaar looks and sounds like Syria’s suqs, though more of the shops have glass fronts. There is a distinctive smell in Aleppo’s markets that I noticed in Antakya, too, some combination of cardamon-flavored coffee beans, roasting nuts and corn, grilling meat, and open barrels of spices.

On the bus back to Antakya from Istanbul, we sat in front of a father and son whose conversation mixed Arabic and Turkish within sentences. As we stood waiting for our bags in Antakya, I greeted the man, explaining that we were living in Aleppo for a few months. He immediately responded with a dinner invitation, which I was sad to have to decline. The amazing propensity toward hospitality seems as ubiquitous among Turks as among Arabs–no national choice necessary.

Thanks to Russ for posting the previous three entries. WordPress.com really is blocked in Turkey!

Victoria’s Wedding

Victoria and Hanna married last night in the Church of Saint Elias, after a ten year courtship. Hala introduced me to her best friend soon after I arrived; Victoria, an Armenian, teaches French at a secondary school in a nearby village. We met Hanna at our party in late September. He is Greek Orthodox, the rite in which the ceremony took place. Hala and Victoria both reassured me that it is no problem for Christians to marry other Christians, regardless of the sect. Marrying a Muslim, they tell me, would be inconceivable, it would alienate their families too much.

There were some 150 people at the church last night, a very recent structure that looked like nearly all the non-cruciform churches I have been inside, with the addition of a large dome. William and I arrived very early–we hadn’t known how long the ride would take, and we didn’t realize that even weddings don’t begin on time. The people from the floral shop were still finishing their work, which was quite extensive. Hanna arrived soon after, looking quite handsome in his charcoal gray suit, if a bit anxious. He explained his nervousness to William. This is a big step–in his culture, he said, you only get to marry once.

The guests stood as the wedding party walked down the central aisle, without music. First the parents, then two attendants, both relatives of the bride and groom. (Huge retinues of attendants, I’m told, are not done here.) Victoria and Hanna walked in together, then stood on the steps facing the priest, their backs to their friends and family. Their attendants stood by their sides, holding candles. Much of the service was conducted in Greek, some in Arabic. (William commented that it was the first time he had heard Allah called upon in church.) One priest on each side of the podium participated in the service, much of which was chanted.

Although there were two completely adorable small children, a boy and a girl, who walked in with the wedding party, neither seems to have been a ring bearer. No wedding rings were exchanged. Instead, around the middle of the ceremony, a priest chanted while he placed a gold crown on Hanna’s head, then more changing and another gold crown on Victoria’s head. He continued chanting as he changed the crowns from one head to the other a few times.

Soon after, one of the priests, swinging a ball of incense, led the couple and their attendants in three circles around the alter. At each pass, the members of the wedding party kissed the cross held by another priest. In half an hour, it was over, the priest blessing them and wishing them health, happiness, and peace.

The bride, groom, and attendants signed some documents, then posed for a few pictures, before processing back down the central aisle to form a receiving line outside. (The church was being prepared for another wedding.)

Victoria was as radiant as a bride should be. She looked completely stunning–and here I wish I had the words that wedding writers used. How would they say it? She wore a long floor-length white gown with a long white train, a fitted bodice embroidered and sequined, with neither sleeves nor straps; her shoulders and arms were bare to the tops of her long white gloves. Her large diamond earrings reflected the light of the many candles that had been lit around the church; actually, they even seemed to reflect her smile! Hala tells me that professionals always do the hair and makeup of the wedding party, and whoever had done Victoria’s was terrific. She is beautiful without it, but looked completely amazing after he (the best ones are men here, she says) was finished.

I was quite curious about what people would wear to a church wedding. Fifty-something women and older wore nice suits and sensible shoes. Only two of us had gray hair. The styles for younger women were remarkably revealing–lots of bare shoulders, more than a few bare backs, shoes with impossibly high heels, a few discrete shoulder tattoos. One woman covered her head. Men wore suits. I’d been impressed in Morocco, Syria, and Jordan that men have such a wide range of types of clothing to choose from, but apparently those are not appropriate for urban church weddings.

Family and close friends moved on to a local club for festivities. William and I returned home in the care of a nice taxi driver (American people are great! he told us. But the president…)

Citadel

It is getting increasingly difficult to get to our place. Some time between June 2006 and August 2007 the city closed the road south of the citadel, making the space in front of the citadel’s entrance a pedestrian mall and expanding the space allotted to the sidewalk cafes. On Friday this week they closed the road around the north side of the citadel as well, with rumors that it is to be permanent. There are few shops on the north side, a couple of cafes only open in the evening, and access to the lower-class neighborhood we live in. There are rumors of an “Aleppo Hilton” to be built on the east side; I wonder what the plan is for the many-hundred-year-old houses here on the north side.

Aleppo Hanging

Five men were hung from the clock tower in downtown Aleppo last week. Some of Ahmad’s French friends came to visit, and expressed horror at the punishment. I pointed out that, in their country where capital punishment is unacceptable, the state didn’t kill people for their crimes. They pointed out though that it was common in the US. I found myself musing about the differences. They actually hanged men–men who had killed strangers after robbing them–in the middle of the day in a visible (very visible) place. We kill people in the middle of the night when no one is watching. Is that to spare the dead future embarrassment? Or to spare the population the knowledge of what is done in our name?

Ahmad was horrified that men killed people, without remorse, just shot them after taking their money. His shock startled me. It is such a common occurrence in the US. It made me wonder about the difference between the two societies. What makes random violence, drive-by shootings, murder so common in the US and so uncommon here (the country my friends and family see as so violent)?

Then our new French friend pointed out that when men kill their wives or sisters on suspicion they have had sex with men to whom they are not married, the murderers were not hung from the clock tower. They seldom suffered serious legal consequences. Why was it different–acceptable to kill women relatives but not strangers?

The question remained unanswered. I did wonder, though, whether “honor killings” (which in no way correspond to Islamic law) would end if men engaging in extramarital sex were considered fair targets by “dishonored” relatives.

Syria hangs five youths in public square (Deutsche Presse-Agentur)